Fridtjof Nansen was one of the great 19th century Arctic explorers. In 1888, at the age of 27, he became the first

person to cross the Greenland icecap, climbing over 9000' and enduring

temperatures as low as -45°. In July, 1893, he sailed

from Norway in the Fram, a specially-designed ice-strengthened

ship on one of the many attempts to be the first to reach

the North Pole. He had read that wreckage from an American ship that

was lost near the New Siberian Islands had been recovered

near the tip of Greenland, seemingly demonstrating the existence

of a westerly ocean current. He decided to sail as far east as possible

and allow his ship to freeze into the ice, and then drift

across the Arctic Ocean in the hopes that it would come close to the

North Pole. By July, 1845, the Fram had only reached 84°

N and he decided to set off across the ice on foot. It was a journey

of incredible hardship and privation, across broken sea

ice that unknown to him was moving southward. At their Farthest

North, Nansen and Johansen reached 86° 14' N, the closest to the

Pole that anyone had ever come, but they were forced to

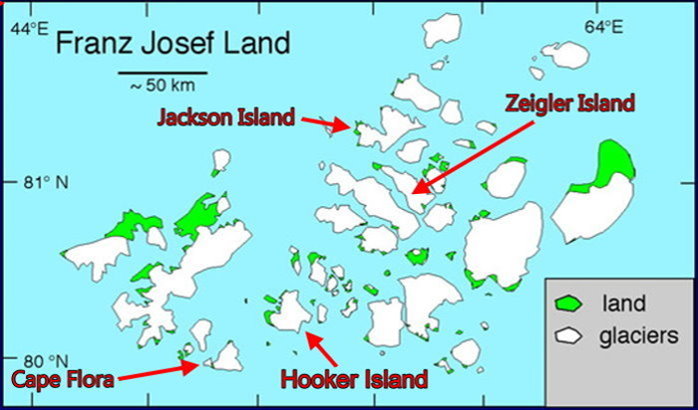

turn back, and 132 days after leaving the Fram came within site of Cape

Norway on Jackson Island in the Franz Josef Archipelago. They managed to survive

the winter and the following summer kayaked southward to Cape Flora

where they met the British explorer Frederick Jackson, who took them

back to Norway. Three years after they left home, Nansen

and the Fram arrived back in Scandinavia almost at the same time, and

the intrepid adventurers enjoyed a heartfelt reunion. Only

someone as strong as Nansen could ever have survived such an amazingly

difficult feat, and the tale of his exploits made him famous the world

over. They had survived attacks by walruses and a polar bear, converted a sledge into a kayak to sail on icy water, proved the polar drift theory, established that the pole was not on any land, demonstrated the advantages of using Sami and Inuit expertise, set a new record for Farthest North, and actually put on weight over the course of the adventure. The remains of Nansen's shelter was lost until 1990

when it was discovered by a joint Soviet-Norwegian expedition. |